The not-so-glamourous origins of standard track gauge

The source of the now familiar 4 foot 8½ inches dimension is often attributed to Romans, wheel ruts and horse’s bottoms, but the real story is far less mythological. GARETH DENNIS takes a closer look.

A version of this article also appeared in Issue 898 (12 February 2020) of RAIL magazine.

Last year, a Twitter thread about the permanent way promptly “did an internet” and went viral. This was as much a surprise to me as it might be to you. And not just because track engineering isn’t credited with being the glamorous profession that I can promise it is.

The 500-word tall tale attempted to describe the origin of American track gauge, how it was defined by Roman roads, “English” wagon builders and horse’s posteriors. It also then suggested that the US space shuttle’s boosters were designed in accordance with this dimension.

As it happens, the story in question was plagiarised in its entirety from an email spam chain that has been doing the rounds in the US since the 1990s. However, speculation over the reason why standard track gauge is, on the face of it, such an odd number isn’t confined to dodgy email spam — in fact, it occurs amongst seasoned railway folks too.

Before we get started, let’s set out the key definition: track gauge is the distance between the inside faces of the two running rails. The “standard” track gauge in the UK and across much of the globe — approximately 55% of the world’s railways use it — is set to 1435mm or four feet and 8.5 inches.

But how did this number come about?

Back in the late 1700s, a range of gauges existed on plateways (early forms of railway) across the UK, including many with spacings between 4ft and 5ft. As early as the 1760s, strips of iron had been used to reinforce old wooden wagonways, but by the 1790s both L-shaped plates and so-called “edge-rails” (relying on a flanged rather than flat wheel profile) were being manufactured in cast iron and laid to allow heavier loads to be transported across terrain where the construction of canals was not feasible.

One such example was the Killingworth tramway connecting and distributing coal from several mines north of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Inspired by early but rudimentary examples of steam locomotives built in the region, George Stephenson (the recently-promoted chief mechanical engineer at Killingworth) developed and built as many as sixteen versions to run on that line and another at Hetton colliery.

Though it wasn’t the most widespread gauge at the time, the Killingworth tramway had been laid with the centres of the original flat plates located a nice round five feet apart.

Stephenson’s designs relied on the friction between a flanged wheel and the edge rail underneath, and so the plateways were replaced with new wrought-iron edge rails. The original plates were roughly 4 inches wide, thus the resulting distance between the inside faces of the rails became 4 feet 8 inches.

As he’d developed his locomotives to be compatible with the Killingworth line, the same dimension between the rails was used at Hetton, too. Incidentally, this line relied only on gravity and Stephenson’s new locomotives, thus becoming the first railway using no animal power.

In 1821, a year before the Hetton line opened, the managing committee of the new Stockton and Darlington Railway decided upon the use of edge rails rather than a plateway (likely under Stephenson’s advisement). Stephenson was later appointed to specify and build the line and its steam engines, and thus reused the gauge of 4 feet 8 inches that he was familiar with.

Stephenson soon moved onto two other projects: the Bolton and Leigh and Liverpool and Manchester Railways. It was the latter of these that was to become the more famous.

Both lines were first specified to use the same gauge as the Stockton & Darlington, but Stephenson found that a slight increase of the dimension between the rails resulted in a reduction in the binding of the wheels through curves without requiring a modification to his rolling stock. Moving each rail outwards by a quarter of an inch resulted in a gauge of — that’s right — 4 feet 8.5 inches.

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway was the first truly modern rail system in the world, including signalling, a timetable, double track and locomotive-hauled traffic only. Its tremendous success shot George and his son Robert Stephenson to fame, and their railways started expanding across the UK.

They weren’t the only engineers building railways, though.

Thomas Grainger emerged as Scotland’s main railway builder and through confusion in his reading of the specified gauge of the Stockton and Darlington Railway (it appears he believed that 4 foot 8 inches was actually the distance between the rail centres) used a gauge of 4 feet 6 inches. In the south west of England, Isambard Kingdom Brunel decided that a wider gauge of 7 feet would allow his new lines to transport goods more quickly.

However, as with many new technologies, an emergent behaviour not expected by the railway pioneers was that trains would travel on more than one railway company’s lines. Breaks in track gauge made this expensive and inefficient. As a result, the Royal Commission for Railway Gauges was tasked with setting a standard track gauge to allow a freer flow of goods and passengers.

By this point, railways laid to Stephenson’s design accounted for eight times more mileage than the next most common design (Brunel’s broad gauge). The subsequent Gauge Act of 1846 therefore selected Stephenson’s gauge as the standard, which in turn influenced the decisions of other major railways across the world…

But what about the United States?

The first railways in the US were built to a variety of gauges by both British and American engineers and, crucially, gauge standardisation in the UK (via the Gauge Act) came well after many of these American lines had been built.

As the railways expanded across the US, several different track gauges gained widespread use, just as was the case in Europe. By the 1860s, there were thousands of miles of track with gauges that didn’t conform to Stephenson’s original 4 feet 8.5 inches — in fact only around half of the railways in the US used this gauge.

Then, in 1861, war broke out.

The American Civil War was the first war where railways played a pivotal role, rapidly moving kit and men around where they were needed most. Changing trains because of different gauges was no longer an annoyance — it was a matter of life or death; of winning or losing.

The predominant track gauge in the South was actually 5 feet. Ignoring the other rather frightening ramifications that such a result would have brought about, had the Confederacy won the American Civil War the US would likely have adopted that as their standard gauge.

So what does any of this have to do with the Romans, their roads and their “war chariots”?

Basically nothing.

There is a litany of problems involved in tying the origin of track gauge to the Romans. As we’ve seen, a wide range of gauges were used by the dozens of different plateways, tramways and wagonways across the UK prior to and indeed after gauge standardisation in 1846.

The wheel ruts that are claimed to match Stephenson’s chosen axle dimensions aren’t really traceable to the Romans, as most of their traffic was foot traffic (they certainly didn’t use war chariots, which had been totally surpassed by cavalry as a mobile military unit well before Roman times). Any ruts formed by post-Roman traffic would have widened significantly over time, allowing for a wide range of axle widths.

The Romans weren’t the first to build decent roads, either. Long-distance ridgeways and other engineered tracks have been in use since Neolithic times, thousands of years before Asterix laid his first punch on a Roman chin. “The Ridgeway” running through Wiltshire, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire is a terrific example and is over 5000 years old.

As for equine rear ends, these vary as much as track gauges did, and indeed ponies, mules, donkeys and children were equally popular forms of wagonway traction.

For those of you unfamiliar with the story I’ve been debunking, it ends with the claim that track gauge influenced the design of the US Space Shuttle’s solid rocket boosters because of the size of the tunnels that the boosters had to pass through on their way from the factory to the launch site.

Firstly: the purpose of a rocket booster is to provide sufficient thrust to get its payload to the right altitude. If the tunnel had been a limiting factor, they’d have been built elsewhere otherwise the Shuttle wouldn’t have worked.

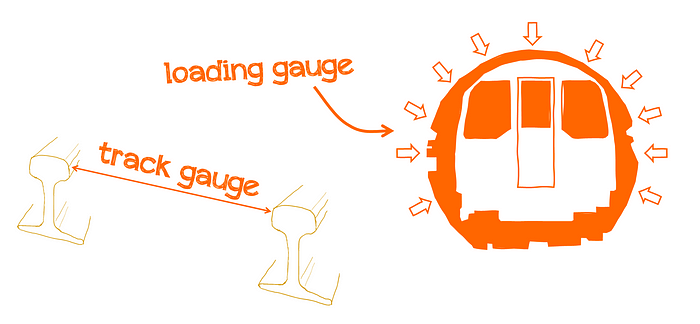

More relevant to rail folks, though, is that this assertion makes an error that I see frequently — a fundamental misunderstanding between track gauge and loading gauge.

Track gauge is the distance between the inside faces of the rails, whilst loading gauge is the available space within which it is safe to run trains. The two dimensions are loosely related but largely independent of each other. Confusing them is the reason that people also suggest, erroneously, that had we stuck with Brunel’s broad gauge we’d have not had the challenges associated with restricted gauge clearance we have today.

Appearing in front of the Royal Commission for Railway Gauges in 1845, Robert Stephenson made the following statement: “If I had been called upon to do so, it would be difficult to give a good reason for the adoption of an odd measure — 4 feet 8 and a half inches.” From the horse’s mouth, so to speak.

In 1905, esteemed fellow railway publication The Railway Magazine reproduced this and other quotes in an article attempting to put the old myth to bed, concluding that “there is no foundation for the Roman chariot tale, and we therefore take this opportunity of nipping in the bud the romance before it has had time to crystallise into a legend.”

Sadly, the authors failed in their aims, and I’ve no doubt I will too. However, I do at least hope that this piece will help provide some assistance to those needing to fight this falsehood in the future.