When it comes to driverless trains, the numbers don’t add up

As part of their latest emergency funding settlement, Transport for London is being pressured into making driverless Tube trains a reality, but how feasible is this? GARETH DENNIS sifts through the evidence.

A version of this article also appeared in Issue 934 (30 July 2021) of RAIL magazine.

Christian Wolmar has written chapter and verse on the pointlessness of driverless cars [Edit: CW was quoted in this piece prior to his expression of harmful transphobic views in February 2023], and I’ve talked about the fact that, when it comes to public transport, the words “driverless” or “autonomous” are usually being used to mask other deficiencies. This was most recently exemplified by the Cambridgeshire Autonomous Metro — a system not confined to Cambridgeshire, that had no actual autonomous features, certainly wasn’t a metro, and I’m pleased to say has now been consigned to history by the recent mayoral elections.

The debate over driverless trains ticks two of my “keen interest” boxes, because not only is this about technology for the sake of technology rather than as a means to an end (as I discussed in RAIL918), but it is also about accessibility and the platform train interface (see my piece in RAIL866).

Let’s look at exactly what the Department for Transport (DfT) have asked of Transport for London (TfL).

In his letter to Sadiq Khan, Grant Shapps dedicates around a page to driverless trains. Firstly, he states that the DfT will lead a joint programme with TfL on “the implementation of driverless trains on the London Underground.”

Secondly, he states that TfL, with the help of DfT, will “make significant progress” (including the commencement of design of new rolling stock, signalling and platform edge doors) in the conversion of “at least one” Underground line to GoA3 operation. More on what this means in a moment.

Thirdly and finally, DfT and TfL are to finish a full review of the potential implementation of GoA3 on the rest of the Underground network by June 2022, upon which future central government support for TfL will be contingent.

I’ll put to one side that TfL is being held to ransom over funding that there’s no reason it shouldn’t have (no other city in the world has to justify the funding of its public transport in this way), but what is equally alarming is that this pressure is being used to force an agenda in lieu of a purpose.

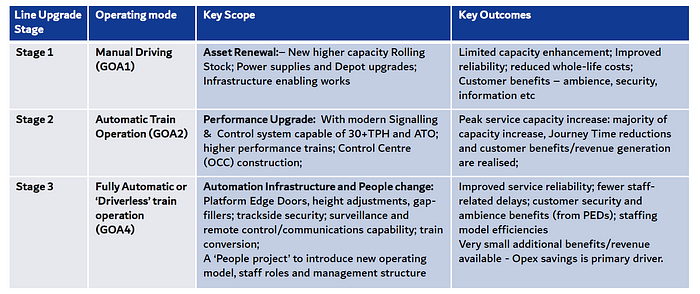

Before I explain why this is the case, let’s look at grades of automation, or GoA levels. These are the most widely applied means of understanding the extent to which a system can be considered “driverless”.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the best way to understand each level is to look at what the on-train person (be they driver or attendee) still has to do. At GoA1, the driver has to start and stop the train to its schedule and operate the doors (amongst other things), as is the case currently on the Bakerloo and Piccadilly lines. At GoA2, the driver only has to operate the doors. Currently the Northern and Victoria lines operate at GoA2.

GoA3 is where the driver can leave the cab and act only as an attendee: they still operate the doors though. In London, only the Docklands Light Railway can operate in this way. To take the on-train person off the train entirely requires GoA4, where automation takes care not only of routine starting/stopping and door operations at stations, but must be able to account for any unplanned circumstances the train might encounter. So whilst GoA3 has no driver in a cab, only GoA4 can be considered truly “driverless”.

Whenever a technology-led proposal is put forwards, the first question everyone should ask is always: “What problem will it solve?” and if the list is very short, then that technical proposal is likely to be without merit. That is certainly the case for driverless private cars, but is it true for driverless trains?

Well, because the ability to operate a train entirely without an on-train person is really a question of managing platform train interface (PTI) risk, not entirely.

The enabling infrastructure for GoA4 (or indeed full GoA3) would result in greatly reduced risk at the PTI because removing train attendees requires all platforms to be set to standard offsets to enable level boarding and to be fitted with platform edge doors (PEDs). It would also require all trains to be built with “low” floors to match the platform offsets and with automatic gap fillers to deal with platform curvature.

Remember: PTI risk is the only passenger risk that is not improving over time, with the number of PTI-associated fatalities and weighted injuries increasing by 7% between 2018 and 2019. The PTI improvements associated with the shift to GoA4 would not only improve safety, but they would also greatly improve accessibility and can also create capacity improvements by reducing dwell times, as recent research by the RSSB (formerly known as the Railway Safety and Standards Board) has shown.

The fitting of PEDs would also greatly reduce the number of suicides on the system (as well as less frequent accidental deaths from people falling off platforms), in turn reducing trauma for station staff.

There are also service benefits thanks to not needing to worry about staff being in the wrong place. Combined with the PTI improvements, this has the potential to provide a minor increase in overall track utilisation (i.e. trains per hour).

However, this does not necessarily translate into greater capacity or journey time improvements on London Underground. Why? Because pushing more trains per hour along a given track does not account for the ability of people to get from street level down into the train. The bottleneck moves from the track into the station, and many of central London’s underground labyrinths had (pre-COVID, though ridership is fast climbing to these levels) already reached excruciating levels of congestion.

What’s more is that GoA4 isn’t needed to maximise track utilisation: the Victoria line, for example, operates 36 trains per hour (tph) under GoA2. This translates to an immense system capacity of 43056 passengers per hour per direction (pphpd). Crossrail, which has the benefit of being an entirely new piece of infrastructure in its central section, will only achieve 36000 pphpd despite operating at GoA3. The limitation in both cases is the ability to safely get people from platform level to street level, and vice versa.

Upgrading the Victoria line to GoA4 would provide no additional capacity benefit without first expanding station complexes, which is planned anyway. Upgrading the remaining Tube lines from GoA1 to GoA2 would provide the vast majority of possible capacity uplift across the Underground system.

TfL’s only current application of full GoA3 operation is the Docklands Light Railway (DLR), but even this system operates under grandfather rights thanks to its lack of PEDs, and with every extension and annual ridership increase comes the chance that the Office of Rail and Road will reassess this derogation (for comparison, the DLR has a maximum system capacity of only 12780 pphpd). Any new system, or upgraded system, operating to GoA3 requires PEDs as a minimum. There’s no getting around that.

And what of costs?

TfL already have a good idea of these thanks to business cases it has already worked up last year, again under direction of the DfT. In 2020 prices and assuming that conversions from GoA1 to GoA2 are already completed, upgrading of the entire Underground network to GoA4 would cost around £11 billion (most of a Crossrail, if you like) accounting for inflation.

This includes the costs of PEDs, new signalling and train control systems, level boarding provision, a train surveillance network, additional guideway security, track raising, changes to depots and stabling, additional equipment rooms and excludes station capacity upgrades or the need to improve emergency tunnel access (which is a bold assumption, frankly).

Now I don’t buy into the argument that capital costs are a reason to avoid strategic upgrades — indeed, I do think that the accessibility alterations required for GoA4 should happen anyway — but given the incremental capacity benefits resulting from the move from GoA2 to GoA4, is justifying the work on the basis of automation going to stand up?

In his discussion of the three “asks” in his letter to TfL, Shapps asserts that driverless trains are allowing other European networks to achieve significant operational efficiencies. As we’ve shown, this isn’t the case: the “efficiencies” come from the enhancements associated with new infrastructure, not from operating at GoA3 or GoA4.

The London Underground is the oldest metro system in the world. It was built to fit the needs of the time, and subsequent upgrades have squeezed every last drop out of the infrastructure. Once you’ve upgraded to GoA2 operation (perhaps with some elements of GoA3 overlaid), the rewards of going further become pretty thin. As John Bull pointed out in his own excellent piece on this subject, there are over 100 metro systems in the world built before the year 2000, and only four of them have been converted to GoA4.

To explain why this might be, I’ll defer to TfL, who state unequivocally in their 2020 business case summary: “None of the GoA4 conversions would cover their costs over the stated asset life.” If central government is squabbling over a few million pounds here and there in its funding settlement for TfL, how likely is it to accept this?

They continue: “Overall network-wide GoA4 conversion represents poor value for money. Its implementation… will present a considerable affordability challenge which will further exacerbate TfL’s current financial and longer term funding position.” Given this unambiguous conclusion, you might wonder why driverless trains are still being pushed onto TfL by Shapps and others. As I’ve hopefully laid out, the answer is political and not technical.