Why aren’t UK hydrogen trains carrying passengers yet?

The race to bring a hydrogen train to the UK market has slowed to a crawl for the same reason blocking conventional electrification: a lack of commitment from government. GARETH DENNIS considers the technological and political hurdles keeping UK hydrogen trains from carrying passengers.

A version of this article also appeared in Issue 940 (22 September 2021) of RAIL magazine.

On the 17th of August, the UK government published its Hydrogen Strategy. Whilst there’s plenty to pore over, the document is undoubtedly a case of the tail wagging the dog, as instead of looking at the required energy sources needed to bring about a net-zero carbon future, here we have a report searching out uses for an existing combustible fuel.

As with all railway matters, it is important to frame any discussion on hydrogen with the bigger picture. There is extensive evidence that hydrogen is being lobbied for vigorously by the existing fossil fuel industry: energy companies and trade bodies held dozens of meetings in 2020 to talk hydrogen with government ministers, compared with zero meetings in 2019. The fossil fuel industry has spent at least €60 million in Brussels lobbying the European Commission on the same subject.

Let’s put to one side the many issues with the strategy (not least its reliance on unproven carbon capture technologies to try and fudge the numbers in relation to how harmful production of “blue” hydrogen is) and look at what it says about rail. In fact, I’m going to quote the entire section on rail verbatim: it is that short.

“Rail is already one of the greenest ways of moving people and goods, and government is committed to making it even greener, in line with our net zero target by 2050. To decarbonise currently unelectrified parts of the network, electrification will likely be the best solution because electrified trains are faster, quicker to accelerate, more reliable and cheaper. There will also be a role for new traction technologies, like battery and hydrogen trains, on some lines where they make economic and operational sense.”

That’s it. Even if you then pick back through the recently published Transport Decarbonisation Plan and Rail Environmental Policy Statement, there are thin pickings for rail and no references to hydrogen train procurement is made.

Herein lies the problem, and it is precisely the same one faced by the rail industry in its attempts to kick-start the decades-overdue rolling programme of electrification… Government refuses to commit its support to anything that requires hard cash over a sustained period of time.

But perhaps we are getting ahead of ourselves: even if an order for new trains was forthcoming, is industry ready to fulfil it?

There are currently only two viable hydrogen train projects in the UK. One is HydroFLEX, being led by Porterbrook with the support of the University of Birmingham and using “converted” (read: totally stripped back and rebuilt) former Class 319 electric multiple units. The other is Breeze, which is being led by Eversholt Rail with support from what was Alstom, using converted former Class 321 electric multiple units.

(I’m going to pass over Angel Trains’ hydrogen train collaboration with Arcola Energy and the University of St Andrews, as it is far further behind so doesn’t really factor into present discussions.)

Okay, so we have two rolling stock operating companies converting British Rail second generation electric trains into hydrogen operation, one relying on the experience of a train manufacturer already operating hydrogen trains, the other leaning on the expertise of one of the UK’s leading rail research centres. Much of a muchness, right?

Having spoken to those leading the technical teams for both projects, there are some notable differences.

The Breeze project is now closely collaborating with Northern, and given that Alstom’s Coradia iLint has been in revenue service in Germany since September 2018 my gut feeling is that this project benefits from a level of frontline operational experience that HydroFLEX does not.

This said, it is the HydroFLEX project that have actually got a hydrogen train running at speed with passengers aboard (indeed, I was one of the first passengers who hopped aboard at Rail Live in 2019!), and with the formidable Helen Simpson steering the project from a technical perspective, I certainly wouldn’t be the one to bet against their chances. This running experience means that they are probably a nose ahead from a technological perspective, having had to live through the pain of running the converted train out on track (indeed, the HydroFLEX train heading to COP26 in Glasgow will be the Mark 2).

My discussions with both teams exposed some interesting points covering the full spectrum of technical and operational challenges. For example, driver training is no more of an obstacle than would be the case for a conversion to overheads or battery as the hydrogen units, at least from the perspective of the driver’s seat, are electric trains.

Traction control technology is being driven forwards, too, as hydrogen fuel cells cannot provide the rapid jumps in power that a driver needs. As a result, systems have had to be developed to enable the spooling up of power in such a way that the fuel cells are not excessively strained or that leaves the driver stuck with sluggish performance.

Arguably, it is the infrastructure to support these trains rather than the trains themselves that is the least well proven — Breeze is being developed as part of a wider Teesside hydrogen economy, but without a set plan for deployment there are still open questions about refuelling infrastructure (and who will deliver it) for HydroFLEX. In both cases, there is an explicit desire to avoid blue or brown hydrogen (the stuff generated via fossil fuels) and to go straight for “green” hydrogen which is generation via electrolysis of water using renewable (and potentially site-based) energy — but can this really be achieved at the volumes required?

Talking of the gas itself, safety is at the forefront, of course, but Hindenburg references are misplaced. Hydrogen as part of a train traction system is no more or less volatile than a tank of fuel or an overheated power unit, as Vivarail — with their converted D-stock trains having caught fire more than once — or indeed anyone who has operated diesel trains can attest to.

Both projects are making no bones about the fact that hydrogen trains are a compromise, and an ugly one at that. Almost an entire carriage of the unit is occupied by the fuel cells and their hydrogen supply, which increases axle loads thus track maintenance requirements and reduces passenger capacity significantly. However, nobody in either team expected otherwise — compromise is the modus operandi of any hydrogen-based system, not least on the railway.

In all, looking across the extensive development that has been completed by both the HydroFLEX and Breeze projects it is clear that these trains work and need to be out collecting mileage. Indeed, both teams are up for a bit of healthy competition — they want to stress-test the work they’ve completed to date. No further meaningful progress can be made without an order being placed for multiple trains that will carry passengers.

And so we come back to the issue of government not wishing to commit to any such thing, despite proposals being submitted by both parties. There’s plenty of big talk — Chris Heaton-Harris is a big fan of the idea of hydrogen trains, and in interviews appears to think they have a potential far beyond those quoted by their developers.

Yet no announcement about procuring even a small fleet of HydroFLEX or Breeze units is forthcoming. The same is true for battery units (which have been pretty extensively trialled already). And of course, we await formal announcement of a rolling-programme of overhead electrification, even if government has said a few times that there really, honestly is going to be one.

The trouble is, making a commitment is something that government cannot delay any further. There is an enormous volume of diesel-powered stock that is going to expire within this decade. In the majority of cases that is long before wires will go up to allow their replacement with fully electric stock, and in many cases (such as for the Sprinter fleet) full electrification isn’t the long-term solution anyway. Seeing as there is no capacity in the supply chain to provide new diesel multiple units, and no desire to procure them within industry, an alternative is required.

Proponents of hydrogen are, for the most part, being pretty clear that their technology isn’t an alternative to electrification. It’s a complimentary solution that quickens the path to a decarbonised railway, the merits or otherwise of blue hydrogen notwithstanding.

This said, the press offices of the main players need to make absolutely certain that they don’t get carried away… Government (read: Treasury) continues to be desperate for excuses to keep the rolling programme of overhead electrification off the balance sheet — thus every release needs to open with the “hydrogen is not an alternative to electrification” line.

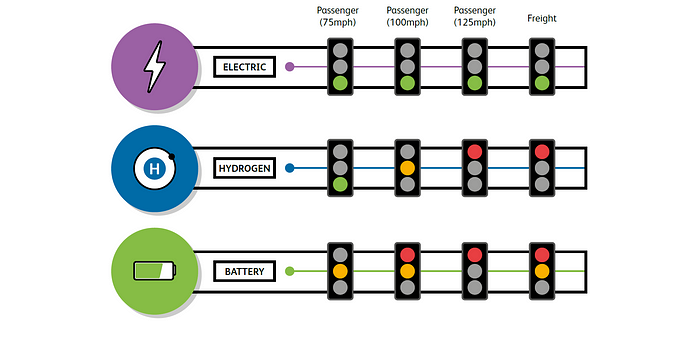

On the flip side, proponents of electrification must be wary not to protest too much. The numbers are clear: wires are the unquestionable solution for at least 85% of Britain’s remaining unelectrified network. But hydrogen has its place for longer-distance rural routes and needs to be matured as a technology.

If those working on hydrogen and those worried that it is an excuse not to electrify speak with a unified voice and are explicit about the scale of the role both must play, it will be even more difficult for government to deny the need for a programme of electrification. Hydrogen isn’t perfect and will always be a compromise, but the railway is built on compromises. If deployed as Network Rail’s Traction Decarbonisation Network Strategy proposes, I believe hydrogen will be a valuable contributor to rail’s decarbonised future.

But a unified voice from industry can only go so far: without a commitment from government to actually procure even a small fleet of hydrogen trains, the technology will remain immature and stagnate. Given that every passing year makes the need for decarbonised railways more pressing, they can dither no more.